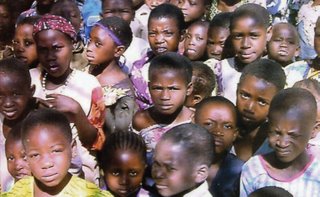

Bishop Katharine receives a warm welcome at the Primates' Meeting in Dar es Salaam. ;-)

Happy feast of Thomas Becket, and a blessed New Year!

The serious and sometimes satirical reflections of a priest, poet, and pilgrim —

who knowing he has not obtained the goal, presses on in a Godward direction.

Somewhere a child is crying.

Lord, help me find him

that I may do my duty to my King.

Led by what dark star

to the outskirts of the capital,

as a man under orders,

commanded, I go.

All of them, he said,

up to the age of two.

I passed one by a while back,

perhaps small for his age;

the soldier behind me thought otherwise.

Soldier. Is this soldiers’ work?

Up to the age of two, he said.

The King is a hard man.

It’s no disloyalty to acknowledge it.

You don’t build a kingdom being soft.

He cuts a broad swath, our King.

All of them, he said,

up to the age of two.

It’s quieter now the screaming’s over.

The cobblestones are slippery

and it’s too dark now

to see with what.

But somewhere up ahead

a child is crying.

Lord, help me find him

that I may do my duty to my King.

— Tobias Stanislas Haller BSG

A mirrorwise reflection between Matthew 2.16 and John 16.2

But the line that has always stuck in my mind is the one with the image of a leader laying hands on the head of a wounded soldier — dare I say, “A little touch of Harry in the night.” In any case, here is my first effort at trying to do justice to this “note” in this very rich Psalm, followed by a few critical comments on why I made some of the choices I did.

This is an offering for all the wounded, for all the casualties. May wars soon cease in all the world, and may our only pursuers be goodness and mercy, all the days of our life.

The Wounded Soldier’s Song

a Psalm of David

1. The LORD is my commander,

therefore I lack nothing.

2. In a green field he causes me

to pitch my camp, resting by calm waters.

3. He restores my life;

he leads me on the right track on account of his Name.

4. Even deployed in shadowlands, I fear no evil,

for you are with me; your baton and your staff give me courage.

5. You set up the mess-tent before me in the midst of hostilities;

you salve my head with ointment, and my cup can hold no more.

6. From now on my only pursuers will be Goodness and Mercy;

and I will furlough for ever in the house of the LORD.

Comments

1. commander: (shepherd — noun and verb — is used as a metaphor for a leader; David himself at 2 Samuel 5:2, Isaiah 44:28 = Cyrus!)

2: pitch my camp / resting (menuha is a resting place for the wandering Israelites at Numbers 10:33, and as “quartermaster” at Jeremiah 51:59) - this is a very “dense” verse

3: life: nephesh is the whole self, including the physical body

track: the ruts of wagon wheels

4. deployed: to “go” as one led.

shadowlands: the dark valley; many scholars reject the connection with “death” but this is my compromise

baton: (as in Judges 5:14, the marshal’s staff)

5. the mess-tent: shulhan is “table” but recognizing the (false) Arabic cognate for “a leather unrolled to form a place to gather for meals in the rough,” the sense of a mess-tent is resonant, and I can’t resist it

hostilities: “those hostile to me”

6. an ironic usage — from now on (for all my life) / pursuers — the sense is that the only “hostile pursuit” will be by Goodness and Mercy — no more enemies!

furlough: w’shavti b’beit adonai = I will return in the house of the Lord; one is tempted to say “demobilized” or “discharged” — but the sense of an “endless leave” strikes the note I’m seeking.

— Tobias Haller BSG

Tobias Stanislas Haller BSG

December 18, 2006

The actual words of the Primates' 2005 Communiqué from their meeting in Dromantine notwithstanding, our understanding of the decision of the Primates was captured in Archbishop Henry Luke Orombi's press release following that meeting: "In our Ireland meeting the Primates suspended the Episcopal Church of America and the Canadian Church until they repent." Therefore, to sit with the new Primate of ECUSA when they clearly have not repented is to surrender commitment and follow-through on a previous decision.Ah, the delicate sound of postmodern hermeneutics at work. The "actual words" which would appear to say one thing, actually mean quite something else. The "actual words" were

we request that the Episcopal Church (USA) and the Anglican Church of Canada voluntarily withdraw their members from the Anglican Consultative Council for the period leading up to the next Lambeth Conference.but they mean, "These two provinces have been supsended until they repent." I am forcibly reminded of Humpty Dumpty's comments to Alice: "When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less." At least we know the spin-cycle is still fully functional in Uganda, as the gyre keeps widening.

I've long ago given up trying to penetrate the translucent mind of ++Rowan Williams! Even his words are, as you see, orphic.

My guess is that this may be an effort to block an end run by Minns. ++Akinola has basically given up on the Network for their pusilanimous refusal to "leave the burning house," and it is ++Akinola who is in the position to make demands of Canterbury. Not that I think he will be successful -- which is in part the message being sent here. In addition, it may be a reminder or warning to ++Rowan's own Church of England dissidents that this will not fly as a way forward.

I also seriously doubt Cantuar would consider +Duncan as a Primate, since the Network has no standing except as loyal members of the Episcopal Church. Besides, he only gets one plus sign. ;-) (I know the Network has spun ++Rowan's comments into whole cloth, but I think they leave out the threads they don't like!) Whatever else Duncan may be, he is not a Primate of the Anglican Communion, and it would take 2/3rds of the Primates voting to make him so. The Panel of Reference report on New Westminster makes it clear that no internal divisions in Canada have been recognized, and that people are members of the Anglican Communion by virtue of membership in their own Province; by extension, no such division is recognized in the US. There is a Primate of the Episcopal Church, and as even San Joaquin points out, they haven't yet withdrawn fully from the Episcopal Church.

All in all, I look to the Primates' Meeting being short some of the more irascible Primates, but hope and pray ++Rowan simply leaves the door open for all Primates of the legitimately constituted Anglican Communion to come, but any to leave. We will then see who it is wants to walk apart.

"The Convocation of Anglicans in North America (CANA) is, to my knowledge, a "mission" of the Church of Nigeria. It is not a branch of the Anglican Communion as such but an organsation which relates to a single province of the Anglican Communion. CANA has not petitioned the Anglican Consultative Council for any official status within the Communion's structures, nor has the Archbishop of Canterbury indicated any support for its establishment." '

Frankly, I don’t know what theological justification there can be for refusing financial help from those deemed unclean. Certainly Israel was instructed to take as much as they could from the Egyptians when they set off on their Exodus (3:22). And I don’t recall the pericope about the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:35) ending,

And when the man recovered from his wounds, and hearing that the one who had helped him was a Samaritan, he cursed the day of his birth, saying, “Woe is me that I should be helped by an unclean sinner.” And entreating the host to cast the coins he had received onto the dungheap, for they were unclean as coming from unclean hands, he wrote letters to his friends in a far country, earnestly desiring that they should send him money that he might pay the host all that he owed.Nor did Jesus refuse the help of the Samaritan woman, though he had better water for her than she for him (John 4:7). So the idea that money from TEC should by no means be allowed to taint Tanzanian hands seems to be a novel idea based on notions of ritual purity; which would explain a great deal.

Now, if this refusal of funds merely meant one less perk for the bishops who passed this legislation, that is, if it really concerned them directly, I would say, fine. But the money these bishops are refusing isn’t meant for them — it is for ministries to the hungry, the poor, the widows and orphans — of which there are hundreds of thousands in Tanzania. The bishops are holding a metaphorical gun to the heads of these suffering hostages, and threatening to pull the trigger unless The Episcopal Church repents and recants. Do you think that image overwrought? We are talking here literally of life and death for many of these innocents. And while going on a hunger strike oneself to force others to an act of conscience is one thing, to make others undertake a starvation strike seems altogether immoral. I don’t know what ethical system these bishops were instructed in, but in my book (you know, the one with an Old and a New part) the primary duty of those who would serve God is to serve the suffering, not to demand adherence to a purity code.

Of course, this is only the latest chapter in the continuing saga of those who think of themselves as holy versus those who do the things Jesus actually commanded his disciples to do. Let me explore one of the earlier chapters with you, and how Jesus dealt with one who thought he knew where holiness was to be found — and not found.

+ + +

In the present debates the story of “The Woman Taken In Adultery” has come up more than once. This episode from our Lord’s ministry, appearing only in some versions of the Gospel of John, and occasionally in Luke, is cited by “liberals” for its notes of tolerance and suspension of judgment and by “conservatives” for its call for reformation of life. As with much of Scripture its one-size message apparently fits all.

There is another gospel episode, however, that I find much more apposite to our present case, called “The Anointing in Bethany.” John (12:1-8) places the scene in the hospitable and somewhat irregular household of Martha, Mary and Lazarus, while Matthew (26:6-13) and Mark (14:3-9) place it in the home of Simon the leper. All three evangelists highlight the extravagant offering of perfume, the diversion of resources that might have served the poor, and Jesus’ response that serving him in this instance takes precedence. (In these cases the Tanzanian and Ugandan fund-refusers might — by a squint-eyed misunderstanding of Jesus — have some remote justification for letting the poor be “always with them” while they serve Jesus directly. Point is, Jesus has now told us, in his absence, to serve him in the poor. Sorry, bishops.)

Luke (7:36-50), however, with his characteristic urge to highlight issues of salvation and redemption, places the scene in the enemy camp, in the home of Simon the Pharisee, whose concern is not with perfume or the poor, but with the woman, or rather, with the sort of woman he knows her to be, not an individual person so much as a member of a despised class of people.

The Pharisee no doubt thinks that he has escaped the snares of sin by his careful observance of the rules. There is no hint that it ever occurs to his purified conscience, “If this man were a prophet he would not accept my invitation to dinner, for he would know what sort of man I am.” No, the Pharisee is prudent; he is temperate. Like his confrère who compared himself favorably to the tax collector, the great gulf between his upright life and this fallen woman’s lifestyle is obvious to him. “Yes,” he might say, “we are all sinners; but some are clearly more sinful than others.”

And Jesus appears at first to ratify this assessment: he offers the analogy of debt forgiveness, forgiveness to one who owed much and to one who owed little. But Jesus doesn’t stop there, with what the Pharisee could well take as a flattering assessment, a pat on the head for his correct answer to the moral drama unfolding at his dinner table.

Instead Jesus presses home the significance of the answer: the Pharisee has judged himself, correctly this time, and Jesus goes on to compare and contrast Simon’s parsimonious welcome with the woman’s lavish and costly service.

The Pharisee welcomes Jesus to the table, but keeps him at arms’ length and sits in judgment — and in error. For Jesus not only knows what sort of woman it is who is ministering to him, but knows it better than the Pharisee possibly can, better than the Pharisee knows himself. The Pharisee cannot fathom why Jesus would allow a sinner to be a minister to him, or at least such a sinner. Of his own trifling sins he cares but little, for he is sure of his own righteousness. But this woman! That is another matter altogether. And so he sits in double judgement, of the woman and her Lord.

She, on the other hand, isn’t worried about her sins, which indeed are many. Nor is there a mention of repentance concerning her tears — unusual for Luke! Rather these are responsive tears of love flowing from faith and hope, from the knowledge of forgiveness, the theology of virtue encompassed and expressed in a woman thought by the Pharisee incapable of goodness, a woman who incarnates and enacts the liturgical sacrament of baptism with her confession of faith, the washing of her tears, and anointing her Lord with fragrant ointment, sealed with the kiss of peace.

So we are presented with two models for our own encounter with Christ, with Christian ministry, with service to the body of Christ which is the church. All who serve the Lord are sinners, all who serve the Lord are forgiven. Some will prefer to spend their time worrying about other people’s sins and how the church can tolerate them. They will seek to obstruct their service, thinking all the while that they protect God’s body from the touch of unclean hands. Others will get on with the works of faith, of hope, and of love. Is there any question at all which Christ would rather have us do?

— Tobias Haller BSG

a sermon preached at Saint James Fordham on Advent 2c — Tobias Haller BSGI’m going to start my sermon today with a question. I won’t ask for a show of hands, but I do want you to be honest with yourselves when I ask it. Ready? How many of us here have ever made use of the snooze button on our alarm clock or radio? How many of us here — if any — can honestly say that when the alarm clock goes off in the morning we pop right out of bed like a firefighter ready to jump into the boots at the foot of the bunk, strap on the uniform and slide down the brass pole?

Take off the garment of your sorrow and affliction, O Jerusalem, and put on forever the beauty of the glory from God. Put on the robe of righteousness that comes from God; put on your head the diadem of the glory of the Everlasting.

Or put the shoe on the other foot: how many of us here haven’t stood at the foot of the stairs or down the hall, calling for the third or fourth time to a son or daughter or niece or nephew or grandchild, “It’s time to get up!” And how many of us have been on the other side of that call — enjoying the extra few moments in bed even more than the whole night that went before?

Well, I don’t think I am alone in this! It is, after all, a law of physics — Newton’s First Law, no less: a body at rest tends to remain at rest unless some outside force acts upon it. And in this case whether the force is an alarm clock or an insistent elder who has made breakfast and is beginning to threaten applying a most definite force to your most recumbent body — there comes a time when you know you actually do have to rise and, if not shine, at least feebly glimmer.

The next thing is that you have to wash and get dressed. And if it is Sunday, you know that you will be expected to put on, not just lounging-about-the-house clothes, not just everyday work or school clothes, but your Sunday Best. You will be expected not just to get up and get dressed, but to get all dressed up.

Nations and peoples act the same way as individuals, of course. Nations and peoples are, after all, just collections of individual people — prone to the same errors and bad habits; the same laziness and reprobation and backsliding — and sometimes the number of people can multiply the problem rather than correct it.

When someone comes along and says to the people, “It is time to get up and get dressed,” it is a rare thing indeed for the people to respond the first time around. It takes repeated calls and repeated warnings before most nations will rouse themselves to do what is right, to do what is just — to do what God calls them to do.

We see this clearly laid out in our Scripture readings today. Baruch calls on Jerusalem to put off her widow’s weeds, to arise and get herself ready and put on her party clothes — assuring Jerusalem that the path is going to be cleared, the hills made low and the valleys filled in, to bring about restoration and rebirth, a new life to the sorrowful land.

But, of course, Baruch wasn’t the first prophet to use such language. Years before, Isaiah spoke in exactly the same way, calling on Jerusalem to awake and arise and put on her beautiful garments. He also described God’s massive earth-moving plan — leveling mountains and filling valleys to prepare the way for a grand procession.

Nor, as we see from our Gospel today, was Baruch the last prophet to use such language. For here is John the Baptist, once again a prophet arising in that old tradition, dressed in the garments of Elijah, announcing once more the promise of God’s highway construction plan — and calling on the people to open their eyes to see the coming salvation of God — and if not to get dressed, at least to prepare for it by the washing of baptism, a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.

Israel needed to hear this wake-up call over and over. For it seems to be a part of the prophet’s fate not to be listened to — hence the need for repetition. People don’t want to listen to the prophets’ warning: remember what happened to John the Baptist! Try too hard to shout-out God’s wake-up call and you’ll get your head handed to someone else on a platter!

Yet Israel desperately needed to hear that repeated wake-up call. And we do too. That is in large part why we continue to hear these passages of Scripture year by year, every Advent hearing anew the call and the promise: the call to rise and shine, and the promise that the new bright garment of grace is there ready for us to don when we have washed away our sins, repenting our past ways and preparing for the great time that lies ahead. We are told that the way is clear — mountains leveled and valleys filled in — not just for God to come to us, but for us to go with God.

The question is — are we ready? Have we risen and washed, and are we dressed? Or are we still lying in the warm cocoon of slumber, with a pillow over our head to shut out the light? Well, we’re here in church — it’s true! But we all know how just as a body at rest tends to remain at rest, a body in motion will tend to stay in motion once it gets moving. So what I want to challenge you and me to ask ourselves this morning is: are we really awake and ready, or are we only sleep-walking? We are dressed up — but have we someplace to go? Are we truly motivated, or only going through the motions? Do we take advantage of this Advent time to examine our hearts and minds, to dig down deep and clean out the rubbish of old habits; to rub the sleep from the corner of our eyes, sweep up the old sins we’ve gotten accustomed to, or the old ways of the world we’ve come to accept as given?

For the world and its peoples love inertia — love to stay at rest, or move along predictable pathways, running downhill instead of mounting the heights. I was listening to a BBC reporter grill UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan earlier this week; and much as I admire Annan, I must say the BBC reporter was playing prophet to his Jerusalem — again and again asking, What use is the UN if it can’t actually do anything to stop the genocide in the Sudan? The powder-blue helmets look very nice, but what use are peace-keepers who don’t keep the peace?

And I would amplify that question, as the genocide continues there in the Sudan, and Northern Uganda is torn with violence, and civil strife is brewing in Nigeria. Do we ever learn? What use is it to say, “Never again” when the powers of this world just press the snooze alarm and say, “Just once more, please”; when the prophets call upon the powers of this world to lay down their swords, and the nations say, “How’s that again?” How many genocides does it take for the world to realize that if it keeps going that way there will be no one left?

The Secretary-General was not without his answer, however, and it was a good one, a realistic one, if not an optimistic one. He said that the UN can only do what people are willing to do. It is not an all-powerful force that can bend the world to its will. As I noted earlier, just as the world is made up of people — and since people are fallible the world makes mistakes — so too the UN is just what it claims to be: it is made up of all those nations, and if those nations individually don’t have the will to act — they will not act collectively. Bodies at rest will remain at rest unless an outside force is applied; bodies in motion, in motion — headed down the same old valleys of disaster.

And this is why, in the final analysis, we will not be able to solve our problems on our own. We will not because we cannot. An outside force is needed, just as Newton said. So this is why, in these last days, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born for us to be with us, born among us — but not merely one of us, but also the power of God incarnate, his way prepared by generations of prophets repeating the same message. Only God in Christ can finally and perfectly rouse us from the slumber in which we lie, even as we seem to be awake. Only he can truly waken us with his bright light, and wash us with the cleansing power not only of water but of his blood, and of the Holy Spirit’s fire. Only he can strip us of the robes of sorrow round us, and clothe us anew with the wedding garment we were meant to wear from before the foundation of the world.

And then, how can we not follow through? How can we not join our voices and raise them, calling out for Righteous Peace and Godly Glory. How can we not call for justice and work for justice, demand that peace be made, and that the innocent no longer suffer — we who have wakened, and who are called upon to rouse our sisters and brothers who still slumber in a world of violence and mischief, a world of hatred and fear, of ignorance and rebellion?

Sisters and brothers, a voice cries out for us to prepare the way of the Lord. A voice calls us to arise and shine and put on our festival garments, to climb to the heights to proclaim what we see. That voice has been calling for a long time, through Isaiah and Baruch and John the Baptist, and countless other prophets since. They point the way to the one who was, who is, and who is to come — the great External Force that can move all our bodies from rest — even from the rest of death — and put them into motion for his purpose, who has called us not merely servants but friends, and clothed us for the wedding banquet.

Let us then this season heed the prophets’ warnings, forsake our sins, be clothed with the garments of righteousness, and greet with joy the coming of our Redeemer and the Redeemer of the world, even Jesus Christ our Lord.+

As I have made clear on a number of occasions, each of you has my prayers if you feel that you must leave the Episcopal Church. You have freedom of conscience but that freedom does not include alienating the property of the church you have sworn to serve.

You and I have undertaken solemn commitments and made binding promises to be good stewards and caretakers of the real and personal property of the Diocese of Virginia and of the Episcopal Church. Those are commitments we are obliged to keep no matter what our future church affiliation may be. I pray that as the persons responsible for maintaining [your] Church, you will keep all of this in mind as you consider your actions as leaders of that parish and fiduciaries of the properties it holds in trust for the Episcopal Church and the Diocese of Virginia.

I pray that together we can reach a resolution to the issues where we differ that takes into account the promises we have made, our obligations of respect and care for one another and most of all expresses our obedience to Christ.

Faithfully yours,

Peter James Lee

Lifestyle choices may play a role in the etiology of the illness, and Anglican Bishops appear to be especially at risk. Additional symptoms include

The ASA (Apostate Specific Antigen) test is indicative, but inconclusive of the exact nature of the underlying pathology. Benign Apostatic Enlargment may be treated with medication, but more serious forms of the disease require surgery.

General Audience, 27 September 2006 (English)

... Wednesday, 27 September 2006 Thomas the twin Dear Brothers and ... went on to Western India (cf. Acts of Thomas 1...

Date: 24/11/06 Size: 12k

All real and personal property held by of for the benefit of any Parish, Mission or Congregegation is held in trust for this Church and the Diocese thereof in which such Parish, Mission or Congregation is located.If a "diocese" were to assert it is no longer "of this Church" it would forfeit the property under this canon, since the property is held for this Church and the Diocese thereof. So when a diocese "leaves" (if it could) or simply is dissolved (as is more likely) the property reverts to "this Church" -- that is, The Episcopal Church, governed since 1789 by the Constitution and Canons of General Convention.

Through utter love in life,

through utter inactivity in death,

in utter response from beyond death into life,

he silences both Martha’s pots and pans,

and Mary’s piety.

— Tobias Stanislas Haller BSG

Thanksgiving Day, 2006

I want to pass along a brief note in recognition of the wonderful work you are doing with the Anglicans these days. Anglicans in general have been rather bland fare for quite some time, but your introduction of some new condiments has a spiced things up quite delightfully. I don’t think I’ve experienced such delectable invective since the late 19th century. Of course, it can’t hold a candle to the Reformation, but it does show signs of promise for a sumptuous feast.

But first of all, credit where credit is due: and much of it must be given to Glumsnaggle, our new IT manager, for the way in which he has managed to transform the Internet from a useful tool for communication into a positive cesspool of trivialization, mischaracterization, libel and slander — and my old favorite, assertion masked as argument. Oh, I never tire of that one. Fortunately, neither do they! Of course, he merely had to guide the process, but it has assured him a place in the Lowerarchy, and I hear he may even be on the Dishonors List.

Along the line of credit where due, I must say you appear to have taken a leaf out of the Enemy’s book, and are becoming positively creative. You have got your patients to the point where they are simultaneously claiming and rejecting authority (of any and all sorts, no less!) without seeing the contradiction. You’ve got them taking each other’s arguments at the very worst, and picking nits like there’s no tomorrow — true enough for some of them, as they will soon discover when they arrive in the Infernal Kitchen.

Just a bit of avuncular advice as you continue your work: by all means keep them focused on themselves, and on institutional questions — Who Gets to Be In Power. I mean, you can be creative as you like with the details, but the “tried and false” methods are always best to Fall back on. I think I do not need to remind you of the First Principle of The Tempters’ Manual, “Remember the Apple.”

Which brings me to my central concern: this unfortunate attention on the part of some of your patients to these so-called Millennium Development Goals. It would really be most unhelpful to our cause to have them actually do the things the Enemy wants them to do, to set aside self-obsession and do something about disease, poverty, ignorance, and so on. Anything you can do to persuade them that these MDGs are just “secular” will be to your advantage. I had a lovely curried Goat last night — one of the Old Souls that I’d kept in reserve; and you know, he still didn’t get it! As I savored him bite by bite, he kept whimpering, “But when did we see you hungry or thirsty or in prison...” Delicious.

So, Nephew, in closing, I advise you to apply yourself to this two-pronged approach: play up the institution and downplay what it is actually meant to accomplish, as it could turn out to be a disaster for us if this movement catches on.

Your Uncle,

Screwtape

I believe this view rests on faulty reasoning. The Chancellor of Pittsburgh raises the issue of the Constitution’s ambiguity, but I believe in doing so he defeats his own claims. For Article VII is only ambiguous to the extent it is capable of being misunderstood, by removing it from its legal and historical context, as has the Chancellor. He claims that the consent of the Diocese to inclusion in a Province is not simply an initial consent at the time of inclusion, but a continued consent for as long as inclusion continues. Had the Constitution been intended to refer only to the initial consent given at the creation of the Provinces, or the initial inclusion of Dioceses within them, he claims that the framers could have stipulated consent “at the time of admission” as part of the Article.

However, what the Chancellor ignores is that such clarifying language was not necessary to convey such a meaning, since at the time of the adoption of Article VII in 1901 initial inclusion was the only meaning possible, since the Provinces did not yet exist.

This Article was the enabling resolution that gave the General Convention the authority to create a provincial structure, and it took a dozen years to realize, when the General Convention finally (in 1913) adopted the Canon actually uniting all of the Dioceses of the Church into Provinces, stating that “the Dioceses of this Church shall be and are hereby united into Provinces” subject to the very proviso of the Constitution upon which the Chancellor makes his incorrect claim — that the diocese will remain in some state of perpetual consent — but which rather ensures that the dioceses will have consented to this action. It was not a question, as the historical record shows, of Dioceses wishing to remain unattached to any Province, but rather having the right to determine which Province they would consent to join. General Convention constituted the Provinces via a Canon — not via the Constitution, which had ceded that power to the General Convention.

Finally, any possible ambiguity about whether to be included means to become or remain a part of a Province is resolved by the legal use of the word consent. For “in law,” consent signifies not a kind of general or ongoing willingness, but “deliberate concurrence in the terms of a contract or agreement, of such nature as to bind the party consenting.”* And, as I addressed earlier with the word impediment, in the context of a legal document (such as the Constitution) words must be taken in their legal sense.

An analogy may be helpful: as with marriage, consent precedes union, and depends upon it. No one would suggest that the legal principle “no one shall be married without their consent” means anything other than that consent is required for and prior to the initiation of the marriage, and once consent is given, and the marriage rite performed, it takes more than a mere change of mind or heart — or unwillingness to abide by the consent once given — formally to end the marriage.

In the present case, it would appear the only body capable of severing the connection of the Diocese with the Province is the General Convention, who has the power to amend the Canon in question — as they have had cause to do over the years with the creation of new Dioceses and Provinces. If Pittsburgh wants a divorce — and if such a thing is possible (other than transferring Pittsburgh to some other Province to which it consents to be joined) it can only be granted by the very General Convention from which the Diocese seems so eager to distance itself.

— Tobias Haller BSG

for the Feast of Richard Hooker: a sermon by Tobias Stanislas Haller BSG

GRANT that we may maintain that middle way, not as a compromise for the sake of peace, but as a comprehension for the sake of truth. — The Collect for the feast of Richard Hooker

There once was a vicar in an English country church of whom his congregation said, “Our Vicar is like God — he is invisible on weekdays and incomprehensible on Sundays.” I hope that I will not in my reflections today prove to be the latter.

Incomprehensible is a synonym for “impossible to understand.” Such understanding can be pictured almost in a physical sense: for to understand is to stand under, as a table stands under what is placed upon it, and so must be larger and more stable than what it holds in order to sustain or support it. To comprehend in this sense is to hold the object of knowledge on the table of ones mind.

Which is why God is incomprehensible. We cannot comprehend God because however hard we try, we cannot wrap our finite minds around the infinite God; God will not fit on the table of the human mind, however rasa our tabula, however much room we make on it, however many leaves we add, because, as the old hymn says, God is broader than its measure.

And the same goes for Truth, if we are speaking of Truth With A Capital T — not just some true things, but the whole ball of wax, the Truth as a full and complete description of All That Is — for the description must be at least as complex as what it describes. Try, for example, to describe a zipper to someone who has never seen one. And when we get to natural zippers like the string of DNA that holds us all together and builds us up at the most fundamental level, the description will take volumes — the printed listing of the human genome, a single transcribed copy of just one DNA zipper, of which we each carry trillions of the real thing in our bodies, would take 200 volumes the size of the Manhattan phone book.

To make matters worse, the truth about what is — even as it is spoken — adds to the sum of what is. If we were to write down even a mere tally of all that is, without further comment or explanation, truly the universe itself would not be large enough to contain all the books that might be written. For the books themselves would add to the substance of the world, and with every word we wrote we would be adding to the subject of our enterprise, and the bibliographers and catalogers would soon have to take up their work. As the wise man said, “Of the making of books there is no end.”

Indeed, the only way to comprehend the Truth, in this fullest sense of the word, and as appears to be the aim laid out in the Collect for this feast of Richard Hooker, is to be outside of all that is. And since only God is outside of all that is, as God is the cause of all being and becoming, so only the mind of God can truly comprehend all Truth.

We get glimpses of this outside-in structure of reality in the visions of the saints and poets — in Byzantine icons and in Dante, and in William Blake too. Perhaps it is most vividly captured in that wonderful vision God imparted to Blessed Julian of Norwich: a God’s-eye-view of the universe, as she saw in the palm of her hand a tiny thing no bigger than a hazelnut, so frail it looked as if it would cease to be in a moment. And God told her, It is all that is, and it endures because God loves it. As Blake would later write,

To see a world in a grain of sand,That is the God?s-eye-view that only the odd mystic glimpses.

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.

Now, in spite of the visions of the saints and poets — who are careful not to mistake these momentary experiences of God’s view of the world for their own accomplishment — most of us are wise enough to know our limits. As Hooker himself put it, “The true properties and operations of [God] are to know that which is not possible for created natures to comprehend; to be simply the highest cause of all things.” (5.53.1)

Yet in spite of this, some in the church from time to time do appear to think they have come into possession of the Truth, which usually turns out to be something far more prosaic and far less visionary — a set of right doctrines, or more commonly, right behaviors. And most of us have the good sense to realize that even this limited claim is a bit presumptuous. We have learned from the hard experience of the church’s history that what you don’t know can hurt you; and that often the church is at its most errant precisely when it claims to be most certain. It is rash for any in the church to claim the ability to see in a glass brightly: especially when the church’s rear-view mirror consistently warns us that objects are nearer than they appear — and we travel at our peril if we imagine that our view through the looking glass is either infallible or complete. Indeed, as we take that backward glance on the ecclesiastical autobahn, we see that behind us HeilsgeschichteStrasse — Sacred Story Street — is littered with the wrecks of time over which God towers in divine incomprehensibility.

Just ask Galileo, Richard Hooker’s contemporary, who set about the task of trying to record a few true things about the world, things evident to the senses, or at least to the senses aided and abetted by the telescope. He suffered the fate of being told that what was wasn’t, or at least wasn’t what he saw it was. Threatened with torture, he recanted and submitted to those who refused to know the truth of what is, so insistent were they on what they thought ought to be.

+++

Those on our side of the Tiber, the Anglicans, by Hooker’s day had learned their lesson the hard way. There had been enough burnings and tortures and beheadings on the scepter’d isle over mutually exclusive doctrines to satisfy the lust for certainty at least for a season. So a “settlement” to continuing vexatious matters emerged from the serendipitous arrival of a monarch like Elizabeth and a scholar like Hooker.

Now, Elizabeth, as a monarch, was probably more interested in compromise for the sake of peace than in comprehension for the sake of truth. She did not wish, as she said, to make windows into men’s souls. She knew that if she refrained from peeping into her advisors’ heads, she could benefit from the wisdom they would share around the privy council table, rather than having to commit those selfsame heads to the block and pike. As long as private opinion on divisive matters was kept in the privy closet, as long as one didn’t ask or didn’t tell, a form of peace could be maintained. Thus what Napoleon would later call the nation of shopkeepers kept the peace by means of compromise, the peaceful coexistence that falls a good deal short of true communion and community, but at least keeps heads on shoulders.

But as our collect reminds us, Hooker aimed higher. His Middle Way was not primarily a matter of compromise, but of comprehension. And the genius of comprehension lies in the breadth of its embrace, and in its confession of and willingness to live with an inevitable degree of error and ignorance. Hooker confesses that since we cannot know all things, and sometimes err in the things we think we know, we must allow room for all things, to make the table not infinitely broad (which is beyond our capacity) but broad enough to hold both the unforeseen and unexpected guest, as well as the uninvited and errant guest who shows up at the wrong party. Who knows, until the master comes, who really belongs there after all?

Hooker directs us to avoid the need for final answers on all but the minimally sufficient, and sufficiently salvific claims of the Gospel, secure truths at the heart of what it means to be Christian: centered on the existence of God, and the incarnation, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ —the eternal Gospel without which there really wouldn’t be any point in continuing the discussion, but beyond which all else is more or less provisional. As he said concerning baptismal faith: “Belief consisteth not so much in knowledge as in acknowledgment of all things that heavenly wisdom revealeth; the affection of faith is above her reach, her love to Godward above the comprehension which she hath of God.”(5.63.1)

So the final answers and the definitive positions on everything and anything, so beloved both by Calvinists and Papists, would give way in Hooker’s view to a more rational willingness to withhold and reserve final judgment on all but a very few core doctrines, to realize that mutually exclusive opinions on other matters cannot both be true — and in the long run neither might be true, and the real truth might lie somewhere else altogether. To cast the net broadly, to make the table wider; to expand the breadth of charity to include all possibilities on matters for which clear and final evidence is yet to be shown: this is Hooker’s rational and charitable mission, a willingness to treat our knowledge as sufficient, rather than complete, and certain, in certain matters, only of its own uncertainty; and above all to trust that all such knowledge and love are securely centered in the depths of God, where the Spirit moves and searches, and where alone wisdom is to be found.

For when one is truly in the communion of the Church, truly united with the other members of the body — which can only truly be a body when all the members are lovingly comprehended in it in spite of differing opinions on secondary matters — Deus ibi est: God is there. Next to this transcendent unity-in-communion all other modified and restricted uses of that word, even the one called “Anglican,” must surely pale in comparison. In the truly comprehensive communion of the whole Body of the Church, the blessed company of all faithful people, we are in God, and God is in us.

+++

And it is in this that we come to the grand reversal, the inside-out of God. Now, generally speaking, reversible garments are notable principally for being unattractive whichever way you wear them. But the inside-outness of God is quite another matter. Here we enter the amazing world — the real world, I might add — in which the inside is bigger than the outside — as observation shows us is true of most church buildings. God’s universe, it turns out, is more like those Byzantine icons or M.C. Escher lithographs than most people are willing to allow. This truth is summed up nowhere so well as in that Johannine avalanche of prepositions and pronouns from today’s gospel.

Jesus starts first from the expected greatness of God: “As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us” — so we are nested in God, resting in the palm of God’s hand like Thumbelina, safe in our hazelnut cradle.

But then comes the surprising reversal: Jesus prays, “I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one,” and suddenly we — made one in the mystical and holy communion of the Body of the Church, the Body of Christ, the temple to which God comes and deigns to be our guest — suddenly we hold Christ within us as he holds the Father within him, nested like a set of Russian dolls with God the Father in the innermost secret room of the human heart, the holy of holies, the privy chamber and closet of good council, and the human image and likeness become the frame to hold the true divine reality behind all that is, among us and within us always.

+++

And in this and this alone is the comprehension of the Truth, the whole Truth, and nothing but the Truth. I said earlier that God will not fit upon our mental tables; but there is one table on which God will fit, indeed, upon which God will fit in a few minutes. It’s right there in the sanctuary. In a few moments, the universe will turn inside out, the heavens will open and God will descend and condescend to be among us and with us, the Spirit will descend upon us and upon these gifts, and we will hold God in the palms our hands, and place God to our lips and, like Mary, become God’s earthly sanctuary. We in him and he in us, will become what we behold, and hold what we become.

Sanctified in this Truth, comprehended in this Body, fed with this food, may we be now and ever one, in the knowledge and the love of God, and the peace of God which passes understanding.

At the upcoming Convention of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, I am sponsoring a resolution to ask the Bishop to authorize the commemoration of John Jay on May 17, using a proper to be developed by the diocesan liturgical commission.

At the upcoming Convention of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, I am sponsoring a resolution to ask the Bishop to authorize the commemoration of John Jay on May 17, using a proper to be developed by the diocesan liturgical commission.Those who only know of Jay from high school American history classes may well wonder why Jay could possibly figure on the calendar of the church. I was in much the same position until an attorney friend and colleague from a neighboring diocese brought Jay to my more devoted attention!

He also pointed out to me that the American Book of Common Prayer’s calendar commemorates no American layman — with the exception of Jonathan Daniels, who was a seminarian. This is not for a lack of people on whom to draw, and among them is John Jay (1745-1829), who as most of us know was a major figure in the early days of American politics, serving in the Continental Congress, on numerous diplomatic missions, and as the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

But Jay was not only pivotal in the creation of this nation, and the peaceful settlement of the Revolution, but in the early constitution of the Episcopal Church, locally and nationally. He supported Bishop Provoost of New York, and was a close friend of the first Presiding Bishop William White, who was chaplain to the Continental Congress that Jay headed as President. As a deputy to the first General Conventions he influenced the development of the church’s political structure in a way that won the approval of the Church of England, and paved the way for Canterbury’s consecration of the post-Seabury generation of bishops. (Seabury’s freewheeling approach had nearly scotched further recognition of the Episcopal Church on England’s part!)

Jay’s influence didn’t stop with the Constitution, however, as he was also blessed to live long enough to become one of the charter members of the Episcopal Church’s first corporate effort: the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society, founded in 1821.

Jay was also a man of high moral principles — not without his complexities — and as the church is called to examine the history of slavery, it is important to note Jay’s early role in ending it, from as early as 1777. He was a founder (in 1785) of the New York State Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and the African Free School for their education. He was a major voice in the debates that eventually led to the phased abolition of slavery in New York State beginning in 1799, with the passage of an Act he was able to sign as Governor. Years later, in 1854, journalist Horace Greely noted that no one could take more credit for ending slavery in New York state than Chief Justice Jay.

It is certainly true that Jay had his faults and was no stranger to controversy. He tangled with Bishop Hobart over the relative merits of denominational versus free Bible societies — and to prove his point was a founding member of the American Bible Society. And unlike the more idealistic abolitionists of the next generation (including his son William), although Jay eventually freed all slaves in his possession, he defended the gradual approach on the pragmatic grounds that liberation without education and skills was of no service to the one set free.

Jay has additional local significance for New Yorkers. He was a graduate of Kings College (now Columbia University), a warden of Trinity Church in Manhattan, and a founding member and senior warden of St Matthew’s, Bedford. It is altogether fitting that the Diocese of New York commemorate the life of this servant of Christ, an exemplar of a layman’s ministry in his tireless work for justice, freedom and peace, as a step towards proposing his eventual inclusion in the calendar of the Book of Common Prayer.

— Tobias Haller BSG

21. The argument that in order to remain "in full communion with the Church of England throughout the world" it is necessary for dissenting clergy and parishes to separate themselves from the diocese of New Westminster, adopting a title for their organisation which implies that they represent the Anglican Communion in New Westminster, in addition to or instead of the diocese and Bishop Ingham, can not be sustained. The Church of England itself remains in full communion with the Diocese of New Westminster and Bishop Ingham, pending resolution of the presenting issue, and therefore with all of its clergy, members and parishes, including those who dissent from its diocesan synod decision but remain in full fellowship with the Bishop and the diocese, together with the dissenting parishes unless they formally withdraw themselves from the Anglican Church in Canada. Even if this were not the case there is no evidence that communion with dissenting parishes would in fact be broken since such provinces which have declared impaired communion have made it clear that they remain in communion with those whom they regard as faithful.The report ends by once again tossing the ball back into the Provincial Court, where by all traditional and legal understandings it belongs.25. The AS critique of SEM elaborates further on the claim, which we believe to be unsustainable in the current situation, that in order for the dissenting clergy and parishes to be in full communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury and the "Church of England throughout the world" it is necessary for special arrangements to be made for them outside not only the Diocese of New Westminster, but outside the Anglican Church in Canada. It is factually incorrect to state (AS 3.4.2.2) that "the province has been suspended from the Anglican Communion until 2008". In fact the Anglican Church of Canada was asked voluntarily to withdraw its representatives from the Anglican Consultative Council until the Lambeth Conference in 2008.

...There is no doubt that the tensions within the Anglican Communion, arising from actions within North America, raise serious and problematic concerns for our future. Yet I am deeply disturbed by the tenor of our approach, as reflected in this communiqué. To me, at least, it appears in places that there is a hidden agenda, to which some of us are not privy. For example, I am unable to understand why there seems to be a deliberate intention to undermine the due processes of the Anglican Communion and the integrity of the Instruments of Unity, while at the same time we commit ourselves to upholding Anglican identity, of which these, as they have continued to evolve over the years in response to changing needs, are an intrinsic part. Thus, for example, recent meetings of the Primates, in which the Global South played a very full part, requested various actions from the Archbishop of Canterbury, which he has been assiduous in pursuing; such as setting up the Lambeth Commission, the Panel of Reference, and now the Covenant Design Group. Yet there seems to be an urgency to obtain particular outcomes in advance, pre-empting the proper outworking of the bodies for which we called.

Patience is a fruit of the Holy Spirit. As Peter writes in his second letter, 'Do not ignore this one fact, beloved, that with the Lord one day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like one day. The Lord is not slow about his promise, as some think of slowness, but is patient with you, not wanting any to perish, but all to come to repentance.' We do not want the best of Anglicanism to be cast aside, and so to perish! And to allow the due processes of these bodies, and the Instruments of Unity, to be followed through will take such a short time in relation to the life of God's Church over two millennia.

I must also say that I am disturbed by the apparent zeal for action to be taken against those deemed not in compliance with Lambeth Resolution 1:10, with a readiness to disregard ancient norms of observing diocesan autonomy. Though this was upheld within the Windsor Report's recommendations, it is of course a practice that was adopted in earliest times by the universal church. It was thus ironic that that the feast of Theodore of Tarsus fell during our meeting: as Archbishop of Canterbury, in 673 he summoned one of the most important Synods of our early tradition. In addressing both the rights and duties of clergy and religious, its decisions included the requirement, already acknowledged elsewhere, of bishops to work within their own dioceses and not to intrude on the ministry of others. We are in danger of giving the impression of being loyal Anglicans, and loyal members of God's One, Holy and Apostolic Church, only where, and insofar, it suits us!

We must also be careful to avoid creating, in effect, episcopi vagantes. This is a difficult and complex area, which Resolution 35 of the Lambeth Conference of 1920 addressed when it said, 'The territorial Episcopate has been the normal development in the Catholic Church, but we recognise that differences of race and language sometimes require that provision should be made in a Province for freedom of development of races side by side; the solution in each case must be left with the Province, but we are clear that the ideal of the one Church should never be obscured.' In our time too, we must do all that we can not to obscure that ideal of the one Church.

I am also more than a little wary of calling into question the election processes of another Province in the way the Communiqué suggests, in relation to the Presiding Bishop of The Episcopal Church. This introduces a completely new dimension into our relationships within the Communion, the reciprocal implications of which we have not considered. I would feel more confident if we addressed this question as a part of the more comprehensive reassessment of the nature of the Communion for our times, which is underway not least through the work of the Covenant Design Group.

An added concern for me is the apparent marginalisation of laity, clergy and bishops in the debate within the Global South. I was particularly glad that circumstances allowed me fully to consult both my fellow bishops, and our Provincial Synod, immediately in advance of the Kigali meeting. For a fundamental and indispensable element of our Anglican identity is that we are both episcopally led and synodically governed. I long for a consultative process that fully engages the whole Body of Christ, recognising that 'to each one, the manifestation of the Spirit is given for the common good' (1 Cor 12:7). Primates do not have sole monopoly on wisdom and knowledge at this crucial time, nor indeed at any other!

However, there are two moral problems and one canonical fault with B033, even as it stands, on which it falls short. First of all, it clearly had to be written in such a way as to avoid the suggestion that there was anything wrong with the election and consecration of Bishop Robinson. This church has made its position abundantly clear that though we may regret the consequences of that action, the action itself was proper. And so this resolution takes up a consequentialist ethic — a position of moral weaknesses. For to refrain from an act one believes to be good out of fear of negative consequences — especially consequences as relatively mild as presenting “a challenge” to the wider church — brings us into the ethically muddy world of utilitarianism — the principle of Caiaphas that weighs morality in pounds of flesh.

The second moral flaw is similar to the first: it is an extrinsic ethic — it is not about the goodness or evil of the act of consent, but what others might think about it. This surely falls well below the standards of Christian morality.

However, the more serious problem with B033 lies elsewhere, in its canonical form.

Our canons expect dioceses to elect persons of godly character, sufficient learning, and sound faith as bishops. Participants in the electing diocese’s convention sign a testimonial to that effect, which in addition assures the church at large that the election took place in due and lawful form.

However, the standing committees of consenting dioceses are expected to have neither direct knowledge of the election procedures, nor of the bishop-elect’s manner of life and learning. Rather, all that the canons expect them, as laid out in the testimonial they sign, is an attestation that they “know of no impediment” to the ordination. This is, essentially, an agnostic statement; it does not designate approval as such, merely lack of knowledge of an impediment.

Now, impediment is a quite precise canonical word; and it means something which renders an act impossible — so impossible that if one were to proceed with the act it would be null and void. This is why marriages contracted in spite of impediments (such as insufficient age, existant spouses, or defective intent) can be and are annulled — no marriage took place because the conditions necessary for it were not present.

A very few people have claimed that a noncelibate gay or lesbian bishop can’t really be a bishop because they cannot be “received by the whole church.” These few believe that the sexual practice of a person is an impediment in the strict sense. This is, however, Donatism in almost crystalline form — not a heresy exactly, but an error that leads to schism. For if a failure in the moral character of a minister rendered the ministry null, who could amongst us sinners, after all, be a minister? Donatism was rejected by the church because it was destructive of an orderly exercise of ministry among and by people all of whom are sinners. No, a moral failing is not an impediment.

Nor were consenting dioceses asked to make such a moral judgment — until B033. And that is where the problem lies: it places this discernment of the character of the ordinand not in the hands of the electors (as the canons expect) but in the hands of the consenters, forcing them to discern qualities that might challenge the wider church, rather than remaining focused on their own personal lack of knowledge of any impediments to the ordination.

Which brings me to the recent election in South Carolina.

A priest who is about to become bishop takes an Oath, in the same manner as at priestly ordination but in a different context, stating, “I do solemnly engage to conform to the doctrine, disciple, and worship of The Episcopal Church.”

South Carolina, in preparation for its election, developed a survey instrument on an assortment of topics for the candidates to submit as part of their review. Here is how bishop-elect Lawrence answered some of the questions.

19. The church should not divide over this [homosexual conduct] issue. Strongly disagree.Bishop-elect Lawrence’s responses are troubling. He appears to say (I will stand corrected if the double negative of question 19 confused him) that the church should divide over the issue of the rightness or wrongness of homosexual conduct. This in itself would appear to be countenancing schism, the technical name for division in the church. The bishop-elect is “unsure” as to whether he would remain in orders if his diocese does not separate from the Episcopal Church — and such insecurity is incompatible with an Oath. Finally, he intends not to remain with the Episcopal Church if South Carolina separates from it. That is, at least, how his answers appear. He surely deserves an opportunity to correct any misapprehensions, or wrong conclusions one might draw from a survey such as the one to which he responded.

20. If the Diocese of South Carolina does not become separate in some formal way from ECUSA, I intend to resign my orders as an Episcopal priest. Unsure.

21. If the Diocese of South Carolina separates in some formal way from ECUSA, I intend to transfer from this diocese to an ECUSA diocese. Strongly disagree.

Whether these survey responses by bishop-elect Lawrence constitute an impediment — and if he stands by them — thus remains to be seen — and needs to be seen — and will have to be judged by those preparing to give — or withhold — consent. Surely his statements are troubling on the surface. But I served on a committee with him at this last General Convention, and he seemed to me to be a man of high principle and conscience. I would pray that he would carefully examine his conscience and his principles in this present instant, and if there is any defect in his intent, mend it, or otherwise not place himself in the perilous position of taking an Oath he may not be prepared to maintain.

— Tobias S Haller BSG